unsettled

Abandoned houses have been my primary subject of study for the last five years. When I moved to northwestern Minnesota for college I became fascinated with the expansive open landscape of North Dakota, vastly different from the populated suburban neighborhoods I grew up in. I immediately began taking road trips all over the state, pulling my car over whenever I saw something from the road that piqued my curiosity. One weekend, my friends and I piled into an old orange Volkswagen bus and drove four hours across North Dakota to an entirely abandoned town I had researched online. We spent the day wandering in and out of houses, creating stories for the strangers who used to live there. After that trip the hunt for abandoned houses became my main focus. Nearly every weekend I was out on the road, scouring the expansive landscape for pitched roofs visible far from the road in the middle of fields.

Every time I find a house I am filled with eager anticipation. Questions flood my mind: Can I get into the house? What will I find inside? What will I find out about how used to live there? Who else has been here? I feel a rush every time I walk through the door or climb through the window of a house, fully immersing myself into a space that was once someone else’s, a space that used to be important, vital, and now is now ignored. For me, these houses are filled with potential for investigation and interpretation.

Houses in rural areas are often affected most by their exposure to the weather and time, and thus, their stories, while obscure and fragmented, seem more preserved from human interference/interaction. Each house is different, with a new structure to investigate, a new interior to scour for objects left behind, and a new narrative to piece together. While the focus on abandoned houses and the surrounding landscape has remained constant, the conceptual content behind each piece changes shifts based on the specific place I explore, the experiences I have while there, and historical information I find through later research. Further, I relish the process of searching and collecting. The tactile nature of my research methods and art-making process, enriches my understanding of history, landscape, the permanent and ephemeral, and the idea of home in the abandoned houses.

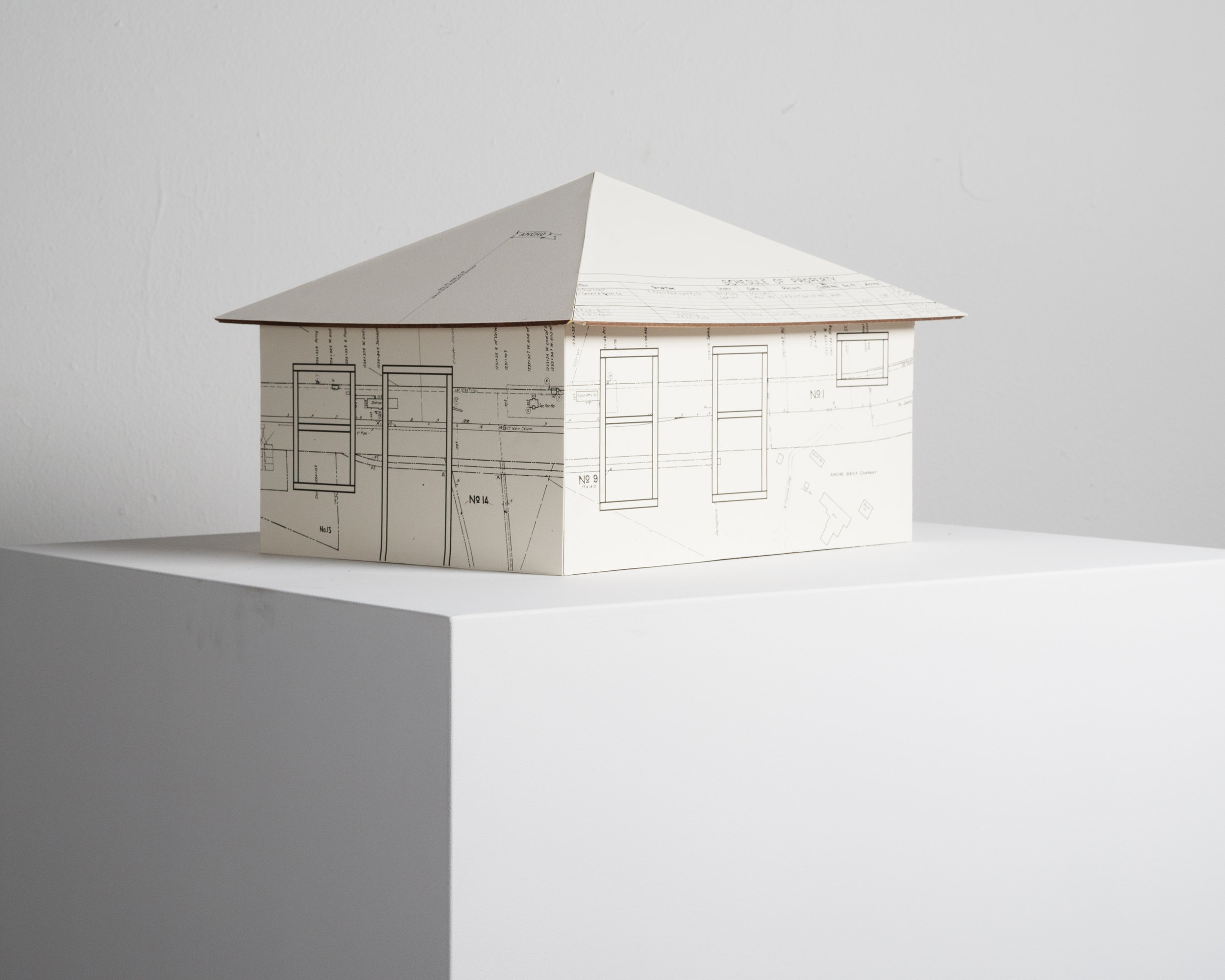

The choice of medium and process play an essential role in both my conceptual and visual strategies. Photography was my first medium and still plays an essential role in my creative process, as I carefully document houses and sites. With printmaking, I am able to add another layer of interpretation and experience that I couldn’t with photography. A year into graduate school, even printmaking seemed to not be enough to convey the ideas my ideas. I was referring to the houses as vessels but only creating two-dimensional objects. After I built my first three-dimensional vessel I was obsessed. I loved the time spent drawing the plans for each wall and roof, and the time spent constructing them. Every side had its own potential to reveal different information. The viewer can navigate the house in space and interact with it in a way not possible with two-dimensional works.

After I moved to New Mexico, the way I experienced abandoned houses shifted dramatically. Unlike the houses I had been exploring in North Dakota, there were rarely any objects left behind for me to use as starting points for connection, attachment, and narrative. Abandoned houses in New Mexico have often been abandoned much longer than the ones in North Dakota, and consequently are nearly or completely empty when I found them. Because I no longer had these objects to rely on, I began thoroughly researching towns and communities through digital and analog archives, old books and dissertations, and even online forums. This information became a necessary starting point for the majority of my work. My work was no longer only about abandoned houses but also about place.

Nearly all of the small, nearly abandoned towns I have visited in New Mexico sprang up in the early twentieth century for steam locomotives, which stopped every seven to ten miles to replenish their water supply. The railroad also brought settlers to New Mexico, claiming land through the Homestead Act of 1862, enticed by the promise of land ownership for a small ten dollar fee and improvement to the land in five years. For many homesteaders their story was one of failure. At first, they could plant crops such as pinto beans or wheat for a few years but then the land was quickly depleted and homesteaders had to become ranchers or move away. The Dust Bowl in the nineteen-thirties, served as the final nail in the coffin for many struggling farmers, ranchers, and often entire towns. Many houses and towns were abandoned because natural resources weren’t adequate for people to sustain life in those areas; they left because they literally could not survive there any longer. While researching the history of the town of Cedarvale I came across a phrase said by a farmer during an interview: “We should have never put a plow to this land.” This phrase has been the cornerstone thought for much of my work over the past few years. The integral connection between abandonment and the quality of land in New Mexico prompted me to consider the connection between houses and land in a more serious and intentional way. It was no longer simply about the house and the narrative I constructed from what was left behind: it was also about the location, the land, what was once there, and what is and isn’t there now.

In the fall of 2015 I took Kirsten Buick’s American Landscapes course which forever complicated and unsettled everything I had felt about these abandoned houses. Suddenly, I was compelled to tackle my own nostalgia and love for these houses, which is inherently a fondness for historical events that displaced indigenous people and misused and destroyed land and resources. I began to see things through a more critical lens and my work began to shift, moving away from my nostalgic attachment to these places, and focusing instead on the frameworks that helped build them, purposefully questioning what role I would fulfill creating work about these houses. As a result, I rely on thorough research to find ways to acknowledge and address the history and failure of homesteading.

Unsettled is a perceptual exploration of the history that is integral to the existence of these houses and my contemporary experiences of them. My aim is to create layered expressions through photography, printmaking, and sculpture that draw the viewer in, inviting them to explore these places and their histories in ways that are similar to my own investigations.